Classifying Folk religions

An estimated 6% of the world’s population, or roughly 405 million people, were believed to be adherents of folk religion according to global survey data amassed by Washington, D.C.’s Pew Research Center in 2010. The total number of practitioners has grown slightly since then, and the Pew Research Center forecasts the population to reach 450 million by 2050. Folk religions and their practitioners can be challenging to identify and measure, mostly because they are less institutionalized than other faiths.

There are commonalities that help identify a religion as belonging to the “folk” classification. Folk religions tend to be closely affiliated with cultural, regional, and ethnic groups. They typically lack formal creeds or sacred texts and persist through rich forms of oral tradition and ceremonial practices. Additionally, they will sometimes integrate elements of more widely practiced organized religions.

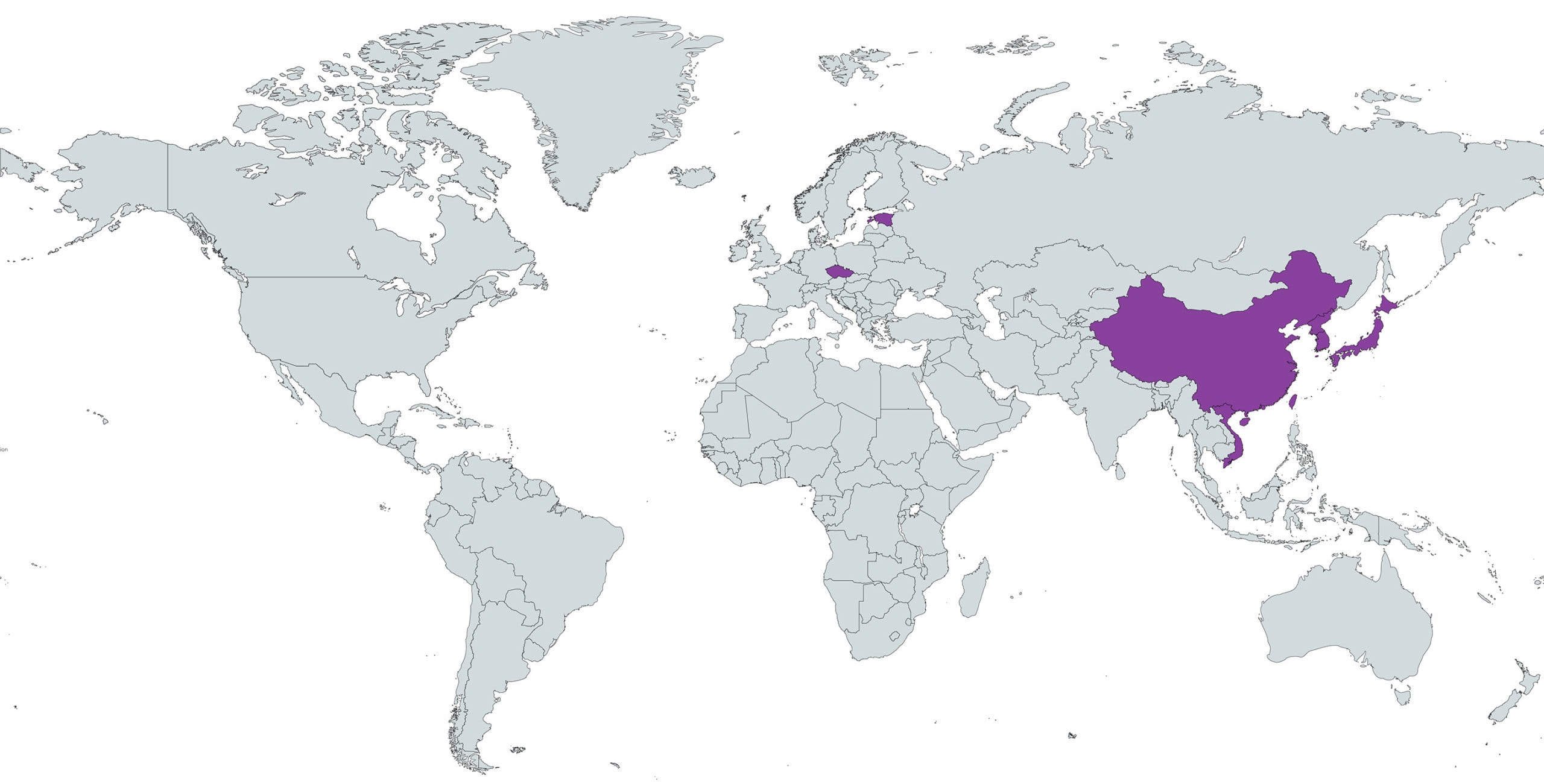

Since folk religions are so multifarious, eclectic, and often regionally and culturally specific, they can be challenging to categorize into broad groups. However, we can identify folk consortia based on nationality and/or culture group. Based on the Pew Research Center data collected in 2010, we know that adherents of folk religion are located most widely in the Asia-Pacific region, where 90% of the world’s folk religious practitioners are located. The other adherents of folk religions are most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa (7%), as well as Latin America and the Caribbean (2-3%).

Shenism

China is home to the largest population of individuals practicing folk religion. Approximately 30% of Han Chinese report practicing Shenism, also known as Chinese folk religion. The Chinese folk faith is closely related to Taoism, but also contains elements of Confucian philosophy, Chinese mythological deities, and Buddhist beliefs. The term “Shenism” broadly refers to Chinese folk religious practices, which are highly syncretic, like most folk religions, and integrate elements from Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and traditional Chinese mythology. Variations of Shenism are practiced in Southeast Asian nations, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Philippines, and Vietnam.

Shenism maintains ancient elements of Eastern religion, including animism (or the attribution of a soul to all living things and sometimes objects) and shamanism (which refers to the belief that shamans, beings with a connection to the otherworld, can heal the sick, communicate with spirits and deities, and escort souls to the afterlife), as well as the veneration of the Sun, the Moon, and the Heavens. Folk religion can be understood as the “basis” for the religious landscape in China and has been practiced for thousands of years, essentially since the start of the Common Era (CE) (Zhang, Lu, & Sheng 2021). Though Shenism is primarily observed on mainland China, it also has many adherents in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Overall, Shenism has around 400 million adherents and practitioners, making it one of the major religions of the world, though it is not perceived as institutional.

In China, it is understood that there are, unofficially, three major religions, known collectively as sanjiao heyi, or the “Unity of the Three Teachings”: Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. An apt metaphor, represented Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism as three pyramid-shaped peaks sharing a common base, which is Shenism, or folk religion. This metaphor indicates, on one hand, that Shenism is practiced by a wide variety of religious individuals in China, and on the other hand, that Shenism and institutional religions are not discrete but instead intersect.

Characteristics of Shenism

In addition to the main Three Teachings, Shenism is heavily related to Chinese mythology and involves the worship of shens (神, shén), which can loosely be translated to “deities,” “spirits,” or “archetypes.” These entities can be nature, patron, kinship, clan, or national deities, cultural heroes, demigods, ancestors, and progenitors. Indeed, some mythical characters from Chinese folk culture have been integrated into both Shenism and Buddhism. For example, the figure Miao Shan, a legendary Chinese princess who became the bodhisattva called Guanyin, is one of the most popular figures to which people pray in China.

Shenism has a variety of localized practices of worship, ritual, and philosophical traditions. Notable examples of ritual traditions embedded within Shenism include Wuism and Nuoism. Wuism is alternatively known simply as Chinese shamanism, and involves the belief that a shaman, or wizard (巫, “wu”) can mediate with deities, gods, and spirits. Nuoism heavily entails the practice of exorcism and has its own system of temples, orders of priests and gods, and rituals. Nuoism is recognizable by its use of wooden masks to represent the gods, and its reliance on yin and yang theory.

Places of Worship

Shenist temples can be categorized as miao (庙), or deity houses, and ci (祠), or ancestral halls. Temples in Shenism are distinct from Taoist temples and Buddhist monasteries in that they are established and administered by local managers, associations, and communities. They are typically small and colorful (in contrast to Taoist temples, which are often black and white, and Buddhist temples, which are heavily red and yellow). They are decorated with traditional figures on the roofs, like dragons and mythical deities. Rituals, sacred re-enactments, festivals, and other practices occur at these temples. One of the most prominent is the Chinese Qingming Festival, also called Tomb Sweeping Day or Pure Brightness Festival, which is very similar to Christianity’s All Souls’ Day.

Political Prejudice in Chinese Folk Religion and Culture

China is not exceptional from other nations in terms of the ways in which religious-cultural and historical influences impact racial perspectives and attitudes. Religious-cultural conceptions of race are reinforced in Shenism and other prominent Chinese religions, the major distinction being between degrees of barbarians, the “black devils,” who are savage inferiors with whom interaction is impossible, and the “white devils,” or the tame barbarians with whom interaction is possible.

At the same time, adherents of Shenism have experienced prejudice in mainland China themselves. In June of 2022, Chinese authorities destroyed some 5,911 temples of traditional folk religion in the Jiangsu province, citing their influence as that of xié jiào or “evil cults.”

Asian and Australian Folk religions

There are different forms of folk religions in other parts of East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific that are Indigenous in origin. For example, in Korea, Ch'ŏndogyo, is a folk religion that combines elements of Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, Shamanism, and Roman Catholicism. Based on data recorded in 2018, 69% of people in Japanese practice Shintoism, a polytheistic folk religion that centered on a massive pantheon of supernatural deities. In Australian Aboriginal religious culture, there are ceremonial practices centered on the concept of the Dreamtime, which is a spiritual realm occupied by nature spirits, heroic deities, and ancestors.

African Folk religions

The continent of Africa is home to a wide variety of traditional and folk religions. They are highly diverse among ethnic groups on the continent, but in general, the concept of animism, which includes the worship of tutelary deities, nature veneration, and ancestral worship, underpins traditional African beliefs.

There is also a breadth of African diasporic religions in various nations of the Caribbean, Latin America, and the Southern United States. These religions commonly involve ancestral veneration and a pantheon of divine religious figures. They also often incorporate elements of Catholicism. For example, Santeriá is an Afro-Caribbean religion based on Yoruba beliefs and traditions, but it also integrates Roman Catholic elements.

Prejudice in Folk religions

While folk religions often emphasize communal responsibility, stewardship of nature, and other highly positive elements, these faiths are sometimes co-opted and weaponized by prejudicial social and political movements. For example, in some regions of the United States, white supremacist groups have appropriated Norse symbols embedded in the Ásatrú folk religion, out of the belief that the Vikings were a “pure” white race. Indeed, one must be cognizant that folk religions are not exempt from problematic, prejudicial, or potentially dangerous features.